By James A. Anderson | miamiherald.com – August 2, 2022

We don’t typically label anything in New York City as out-of-the-way, not with 8-plus million people crammed into as dense a concentration of artists, shakers, business movers, celebrity restaurants and gleaming skyscrapers as you’ll find on Earth. Brace yourself, then, for Woodlawn. A cemetery at the very northern edge of the Bronx, Woodlawn is physically just 14 miles from the city’s epicenter at Central Park, a 40-minute ride by subway. The trip here is a leap into a parallel universe. Within a few hundred feet of the entrance at Jerome Avenue, a wooded enclave starts to overpower the city’s grit. The threshold opens onto a hallucination: The 400 acres before you are a lush, resplendent green, suffused in a fanfare of blossoms during the spring and aflush in autumnal red, gold and ochre in late October and November when the leaves turn. Farther in, you will find a small lake lounging behind the trees, adorned in reeds and cat o’ nine tails. Ducks sun themselves there while wild turkeys graze nearby.

Woodlawn may feel off the grid, but it is unparalleled as our nation’s foremost tribute to the brightest luminaries of the African American pantheon. The cemetery was designated a national historic landmark in 2011, and for U.S. Blacks, it roughly parallels what Westminster Abbey and Pere Lachaise are to the historical, artistic, political and economic heavyweights of England and France, respectively. You’ll find Nobel laureate and career diplomat Ralph Bunche, a man who was present to help launch the United Nations. He later helped advance the push to end colonialism in Africa, Asia and across the globe. Madam C. J. Walker — a self-made millionaire who created a signature brand of beauty products — is here as well. Some celebrities of lore, like Bert Williams, seem obscure today; he was all the rage 100 years ago, however. Williams was the first African American film star and leading man on Broadway and one of the foremost Vaudevillians of the early 20th century. Celia Cruz, the queen of Salsa music, has a mausoleum. Add to the list Matthew Henson, who accompanied Robert Peary on his famous expedition to the North Pole.

Woodlawn is strangely alive with the rhythms and contradictions of a city that has been the nation’s cultural and commercial life force. In the mid-19th century it was envisioned as a sanctuary apart from Gotham City and has since matured into its own miniature ecosystem. Over 140 varieties of trees thrive on the grounds, including oak, beech, elm, hemlock, popular, pine and cherry. Together, they earned the cemetery the designation as an arboretum. The Audubon Society recognizes Woodlawn as a unique bird habitat for woodpeckers, owls, hawks, herons, and kingfishers, and it organizes bird-watching tours here in the spring and fall. There’s a strange tension here, though. For all its abundance, Nature has to compete for your attention with mammoth monuments designed by some of the foremost architects of the 19th and early 20th century. The otherworldly mausoleums at the Jerome end of the cemetery’s vast grounds were commissioned by tycoons, magnates and robber barons, whose names were among the American elite of the Golden Age: Gould, Macy, Westinghouse, Armour. Look in one direction, and there’s tarnished teal of a bronze dome that resembles a magnolia pod atop marble columns. Off to the right, there’s a replica of a French cathedral that da Vinci designed. Nearby, two granite sphinxes guard the entrance to a white granite Egyptian temple.

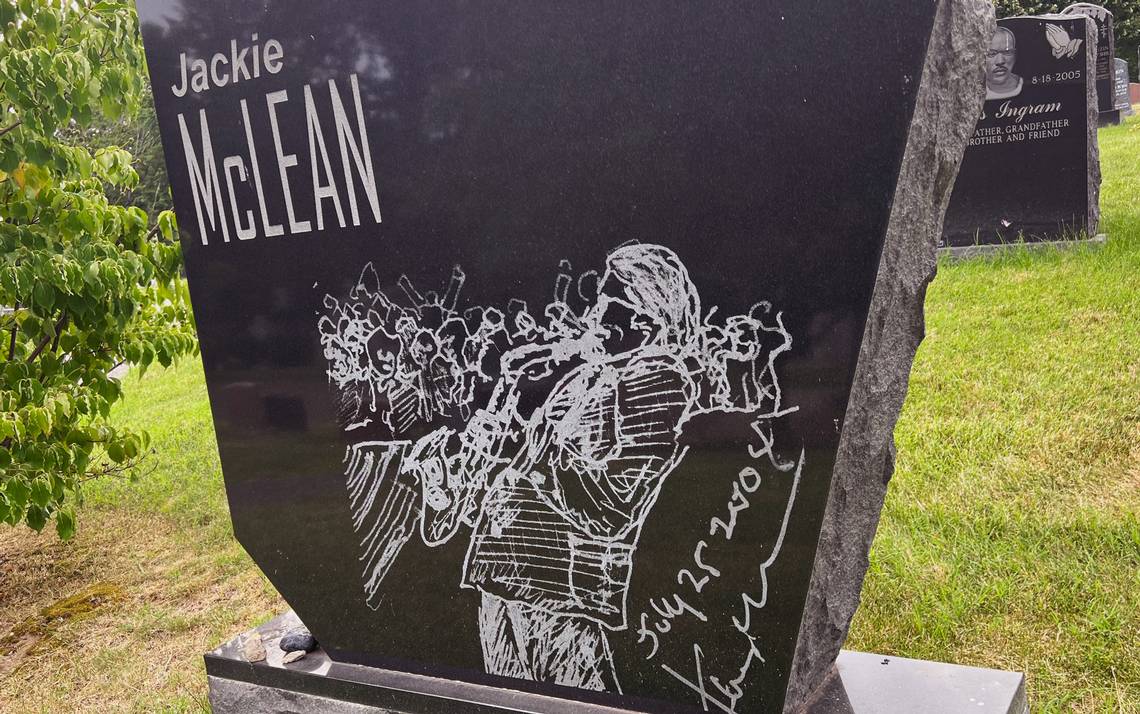

Visiting Woodlawn is more than a chance to get your gawk on. In an unassuming way, it has reserved its loftiest homage for America’s jazz greats, many of whom are clustered in a slightly humbler corner of its confines. Duke Ellington, the bandleader who held classical aspirations for African American music, is found alongside his family at the head of the cemetery’s jazz corner. It is fitting that Miles Davis, the mercurial catalyst whose body of work stretches from Charlie Parker to Prince, is just across a slender pathway: Reputedly, Miles once said Black musicians should thank Duke every day, and now he has his chance to amply express his gratitude. There are other Jazz stars gathered close by — Milt Jackson, Max Roach, Lionel Hampton, Coleman Hawkins and Jackie McLean — most within earshot. Don’t forget George Wein, the jazz producer and promoter who founded the Newport Jazz Festival.

The unsung hero of this narrative, however, is W.C. Handy, a musician and composer buried in Woodlawn who has gone criminally neglected during the past century, even if he managed to gather up a bit of his due in the decades following his death in 1958. Handy’s claim to fame is unmatched in 20th century: discovery of the secret that made African American music a commercial powerhouse. Handy is the inventor of the 12-bar Blues, a structure that became the skeletal underpinning of rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, soul, jazz and every imaginable permutation that came — or was sampled — afterward. In large part it was the driving force behind recording industry profits for the next 100 years. From a 21st century perspective, we’d call his invention an algorithm, a code that magically distilled an African American folk art — in this case the genre called the Blues — to a concentrated, finite pattern that could be infinitely replicated and yet endlessly open to artistic interpretation.

Handy’s creation was unveiled in the early 1910s and featured in two songs he penned – “Memphis Blues” and “St. Louis Blues.” Both included a chorus that used the signature 12-bar pattern. There is no overstatement of what Handy’s idea made possible. When women singers Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey got hold of the catchy 12-bar form, their commercial success swept aside preconceived notions about Black music and its marketability. The breakthrough ultimately reshaped the music industry into a money machine that reaped some $15 billion a year by 2000. Yes, Handy received a Grammy in 1993, but he deserves far more. Handy’s headstone is found in a surprisingly unassuming part of the cemetery, one where a cluster of apartment buildings quietly eavesdrops in the background.

A visit to Woodlawn is a layered and nuanced experience that juxtaposes the vibrancy of this life and the ethereal essence of the beyond. It is worth a gander even before you visit the cemetery: The conservancy that manages Woodlawn has prepared online virtual tours. Guided tours are held throughout the year and jazz concerts are booked during the summer. An insider tip: If you feel the urge, there’s a way to pay your respects to the greats like Handy, Duke and Miles. Leave a small pebble or stone atop their gravestones. The gesture is borrowed from Jewish tradition. It is both a form of silent applause and evidence of African American music’s lasting universal appeal. What better way to cap a trip off the grid and into the marvel that is Woodlawn?