By Daniel J. Fernández-Guevara | Perspectives on History – January 13, 2023

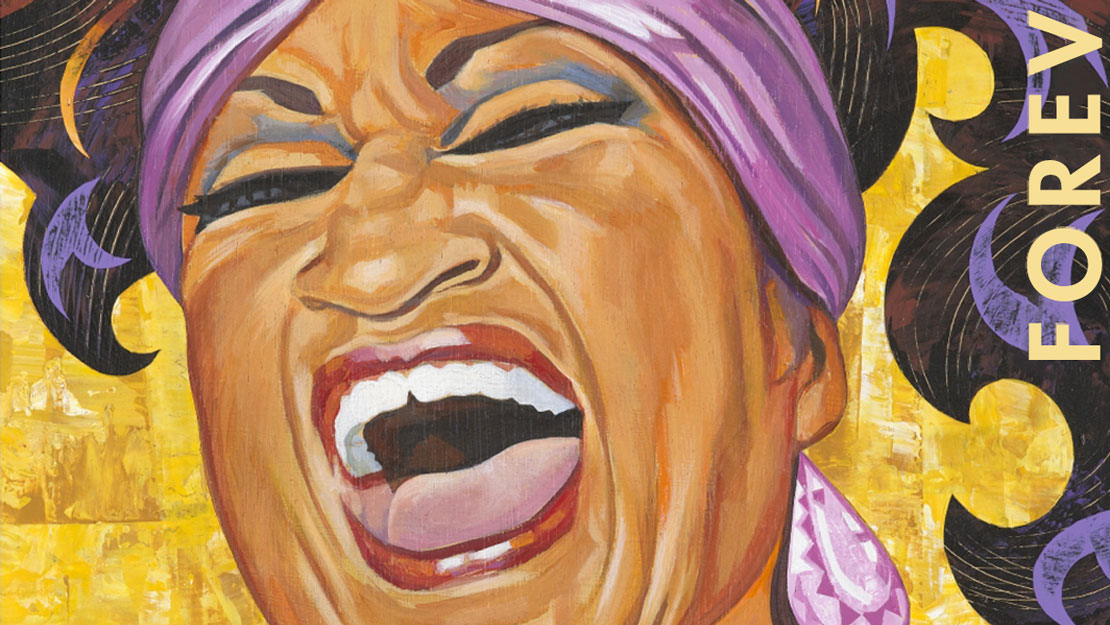

Celia Cruz and Cuban Exile Memory

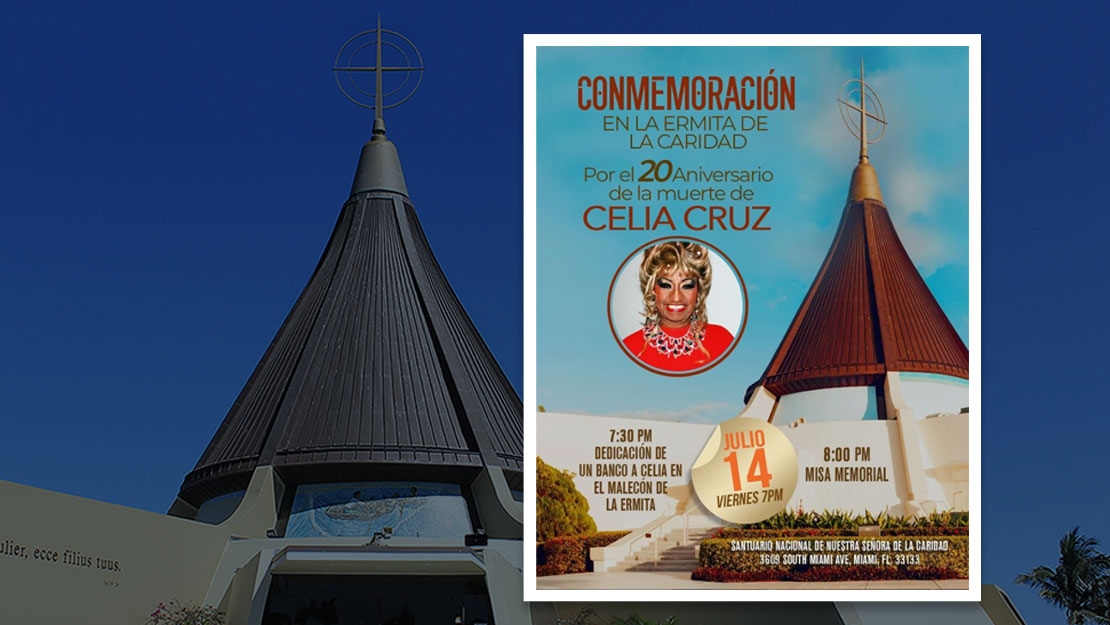

As the 20th anniversary of her death approaches in July, Afro-Cuban musician Celia Cruz is once again back in the headlines, as are simplistic renderings of the artist’s life and music. The memories of Cruz contained in these news pieces reveal how collective diasporic memories can sometimes gloss over inconsistencies in exile narratives of success, producing a group amnesia about the context and content of artistic interpretations. Cruz’s popular appeal enfeebled possible critiques, and most importantly, an honest examination of the artist and her music.

Born in the tenements of Santo Suárez, a working-class Havana neighborhood, Cruz became a star during the 1950s as the lead singer of Cuba’s most important swing band, La Sonora Matancera. She did so despite deeply ingrained racism and sexism on the island. Following the Cuban Revolution of 1959, however, Cruz famously left Cuba to tour Mexico in 1960 and never went back. She settled in the United States, where she composed 34 studio albums, won numerous awards, and even earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1987. Although she died of cancer in 2003, the “Queen of Salsa” remains beloved by fans of diverse national, racial, and ideological groups.

Cruz has long been a particular darling of the Cuban American exile community, an oddity given her importance as a Black cultural figure and the exile community’s overwhelmingly white membership. To them, her musical greatness after 1960 testified to the belief that “free” Cuba prior to the 1959 revolution had produced the most significant contributions to the island’s culture, worthy of global recognition. Her success abroad in turn served as a symbol for a triumphal, anticommunist rags to riches story of postrevolutionary exile. Cruz’s love for her unreachable homeland was unquestionably a central feature of her persona and of her appeal to Cuban exiles, beyond factional and internal political divides. But Celia Cruz as a unifying anticommunist symbol does not match her personal behavior, which could have been considered tantamount to treason by many of her more conservative fans in exile. This image also simplifies her own more complicated political history, and with it, the political history of the exile community itself.

Celia Cruz as a unifying anticommunist symbol does not match her personal behavior.

Cruz’s former manager, Omer Pardillo Cid, has leaned into the exile community’s memory of Cruz since her death, telling Billboard in 2016 that she “was the exiles’ flag.” According to Pardillo Cid, Cruz requested permission to return and bury her mother in 1962. When the Cuban Embassy denied her visa, she declared, “If I can’t return to bury my mother, I’ll never return.” Yet this absolutist narrative does not match Cruz’s discography. From the late 1960s onward, she kept recording songs about a future return—not under the exile’s conquest, but through reconciliation. These included “I Will Return (Yo Regresaré)” (1969), “Paths to Return (Caminos Para Volver)” (1983), and in one of her last recordings, which hinted at her own mortality, “In Case I Don’t Return (Por Si Acaso No Regreso)” (2000). In the latter, Cruz spoke directly to Cuba, affirming “soon the moment will come that erases the suffering. Let us hide the resentment, dear God, and we can all share the same feeling.” These were hardly dominant views in parts of Miami, where resentments of past injustices led to calls to “wipe out” Cuban government collaborators. Cruz’s contrasting calls for reconciliation are perhaps best explained by examining her own personal evolution.

Cruz was not always an anticommunist symbol, as the songs in her repertoire and Cruz’s personal history attest. In 1959, Cruz sang a song titled, “Peasant, Your Day Has Come (Guajiro, Ya Llegó Tu Día)” in support of the revolution’s agrarian reform program, a measure that led many would-be exiles to oppose the Castro regime. A 2004 Miami Herald article even revealed that American authorities banned Cruz from visiting the United States during the 1950s on suspicions of her communist sympathies. Cruz apparently belonged to Cuba’s Socialist Youth movement during her 20s. Violating the hardline Cuban exile taboo of engagement and amid clamor for greater isolation following Cuba’s economic collapse in the early 1990s, Cruz’s album Irresistible featured two songs written by island musicians who continued to reside in Cuba and defend the revolution. Yet her personal history also allowed her to straddle factional divides. For many exiles who arrived in the United States after 1980, Cruz’s former militancy mirrored their own political evolutions from revolutionary sympathizers to opponents. Cruz’s songs promoted the island’s artists to exile audiences, and her song choices received no censure from leaders of the exile community.

Cruz enacted her brand of reconciliation by engaging with many of the island’s most progovernment performers in private, yet the Cuban government forbade any recognition of her music. Before the 2010s, Celia Cruz was barely known in Cuba despite her immense popularity before 1959. In fact, she became a superstar almost everywhere except Cuba after 1960, performing for audiences of more than 80,000 in Kinshasa, Zaire (1974), and 250,000 in the Canary Islands, Spain (1987). While Cruz’s music has since been played on Cuban radio stations and she is finally posthumously getting greater recognition, her absence from the island influences the way Cruz is claimed and consumed on and off the island.

Her absence from the island influences the way Cruz is claimed and consumed on and off the island.

On the cusp of the 20th anniversary of her passing, commemorations are already trickling in. In 2018, West African singer Angélique Kidjo kicked off the homages with a tribute album and high praise for Celia’s influence on her homeland’s music. The 2022 Coachella Festival featured Cruz’s music in a tribute to Latin icons, and Puerto Rican reggaeton pioneer Ivy Queen told Rolling Stone in March 2022 that Cruz’s “influence is felt even though she’s not here with us anymore.” Cuban-born American pop singer Camila Cabello features a song called “Celia” in her 2022 album Familia. In this song, Cabello can travel to Cuba while in exile through Cruz’s music.

As the inevitable tributes come over the next year, we should consider the liminal space that Cruz’s music occupies between longing and belonging, centering the desire for reconciliation that unites Cubans of most political stripes. Odes that characterize Cruz as the exiles’ standard-bearer should examine more closely the dissonance between the hardline anticommunist icon and her personal and musical choices. As historian Mike Bustamante writes in Cuban Memory Wars, polarized interpretations of the island’s past “continue to square off. . . . But dig beneath either iteration of the tale and less streamlined or comfortable narratives of Cuba’s history emerge.”