By Milena Recio / oncubanews.com – April 21, 2022

The least known stage of this world icon of Cuban music was spent in Cuba. Musicologist and biographer Rosa Marquetti Torres reveals to us details of Celia Cruz before she left the island.

On Friday, July 15, 1960, Celia Caridad Cruz Alfonso flew from Havana to Mexico City to fulfill one of the many artistic commitments she used to have. At 35 years old, as a recognized soloist and female voice of La Sonora Matancera (one of the main Cuban orchestras of that time), Celia Cruz was already a star; a star that would be born again.

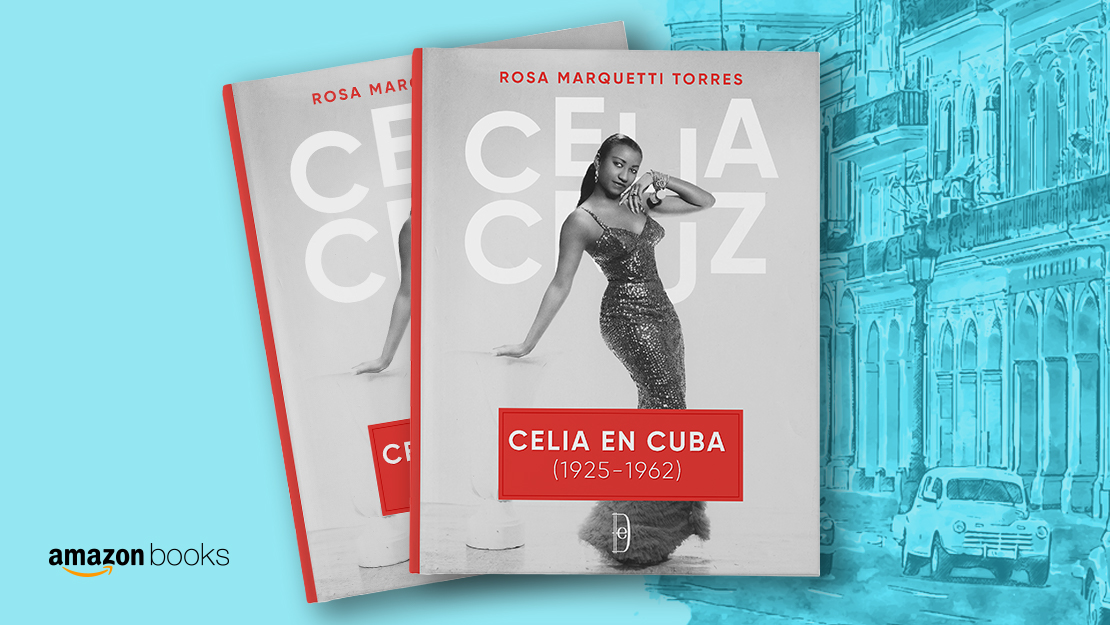

It ended being a one-way trip, from which the musicographer Rosa Marquetti Torres begins her story in Celia en Cuba (1935-1962), her recently published biographical book dedicated to a fundamental and little-known part of the life of «La Guarachera de Cuba».

It is a story that spans from the time she came into the world as the daughter of Ollita and Simon, until she saw for the last time «the sun of Cuba shine in that sky,» as Celia herself would tell in her memoirs.

«That day closed the original cycle of one of the most relevant and successful careers that a Cuban singer has ever had,» writes Marquetti Torres in the first pages of the book, available on Amazon under the Desmemoriados Project label.

During the following year and a half since her departure from Cuba, Celia Cruz would see that her music and her art could grow in the United States; she would immediately be invited to give concerts on important stages of the Union, with enormous success.

A great door opened there, while Cuba, where the Revolution had just triumphed, represented many new uncertainties for those who made cabarets and dance halls’ nights shine.

The final outcome of this period was without any doubt her mother’s passing in Havana and the impossibility of her returning to Cuba to be with her, something Marquetti Torres investigated. These events ended up deciding Celia’s fate.

The «Queen of Salsa», this woman born in Santos Suarez (Havana) and veiled in an apotheosis of love at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, trained to be a teacher and owner of the most recognized female voice of Cuban music in the rest of the world, remains, however, an undiscovered reference for many Cubans on the island. We are still far from Celia.

The political dispute marked her life and ours. In her epilogue, Marquetti Torres acknowledges that being «at the mercy of the most intransigent thoughts and tendencies of the two contending forces in the Cuban national conflict, her great internal struggle would lead her, on the one hand, to express, in the best way she knew, her patriotism, her sense of belonging and love for Cuba (…). On the other hand, she tried to weather the best she could —not always with success, not always effectively and I’d dare to say not always sincerely— the intolerance of those on both shores who were moved by political interests».

Adding up her two lives, inside and outside her beloved homeland, Celia became «a universal reference for Cuban music and an inspiration for Latin American and Afro-descendant women, as an ideal of self-improvement, effort and triumph.»

When and why did you start this research? What convinced you that you should do a book like this about Celia in these times we live in?

You know my line of work from my blog Desmemoriados – Historias de la Música Cubana: what I pursue is to overcome oblivion and leave information and assessments as correct as possible in a digital space, which several generations already recognize as their main source of reference.

Although there are several books about Celia, none is signed by a Cuban author, none is published in Cuba, which may be a debt to the most important and universally transcendent female figure in Cuban music.

Our gaze as Cubans was needed; and it was and is necessary to overcome the ostracism to which Celia has been condemned in her birth country. That’s why in January 2018 I began this investigation.

Why did you choose to cover only her period in Cuba?

It is the least known in his career, the least studied, the least written about. The reasons are various. Celia herself avoided delving into her years in Cuba, and limited to essentially emphasizing her work with La Sonora Matancera. But it was necessary to dive into her formative period, where it started, developed and consolidated one of the most impressive careers that a Cuban singer or musician ever had.

It was necessary not only to expose, but also to dismantle the mantras that circulate according to which Celia Cruz was made by Johnny Pacheco and Fania Records. I wanted to expose and demonstrate that when Celia arrived in New York she was already one of the most complete, famous and respected singers; she was a prophet in her land.

In your book, you explain two facets of Celia Cruz’s life that ordinary Cubans ignore or out of which we have a distorted image: the first is Celia’s rise in her career in Cuba and how she was already a star before leaving the country, along with all that it meant for a young black woman in a male-dominated environment.

The concept of professional triumph and its materialization in Celia Cruz has a remarkable meaning as a legacy. There aren’t many examples of black women emerging from the most impoverished social strata and, on their own, winning recognition and respect in a deeply patriarchal and class-oriented society.

Beyond her innate talent and friendliness, Celia’s personality traits such as perseverance, discipline, sagacity and a sense of opportunity come together and develop. She had in her favor the fact that her family support —from her mother Ollita and her aunt Ana— instilled a strong self-confidence in her, and the certainty that, through talent and perseverance, acceptance and triumph were possible.

She had to deal with many demons: in the 1940s, when she debuted as a professional, the genres she assumed were mostly carried out by male singers.

In preserved records from those years you can sense a strong influence of singers as Orlando Guerra «Cascarita» or Miguelito Valdés in the phrasing, improvisations, textual appoggiaturas, etc. But Celia found the way to quickly overcome that in the search of her own style.

Actually, the atmosphere of the bands was so manly that Seeco Records’ owner himself refused to record Celia for commercial purposes, arguing that women couldn’t sell records. Only the strong defense of Celia by Rogelio Martínez, director of La Sonora Matancera, made it possible for the American to change his mind.

In the live performances during the first weeks of her debut with La Sonora Matancera, Celia was rejected by the public, who preferred her Puerto Rican —and white— predecessor Myrta Silva. Nothing daunted her. She continued her path of improvement and perseverance and in a short time the public came to adore her.

Upon arriving in the United States, she already had a triumphant career in Cuba, widely recognized. It was in Cuba where that process of personal and artistic growth and consolidation of values took place.

I think a second finding for readers will be knowing and understanding the context in which Celia leaves Cuba, for reasons that were not strictly political, contrary to what is usually thought…

Politics is in everything, it influences everything. But yes, it must be said that when Celia went on that flight with the other members of La Sonora Matancera to Mexico on July 15, 1960, she was not consciously and deliberately going «to remain outside» or «into exile.»

Neither she nor almost anyone in 1960 thought about leaving Cuba forever; the idea that they wouldn’t ever return did not cross their minds. Many of us still living can recall that back then it was common to hear among those affected by the new Revolution’s policies, that «the Americans would not allow a government like that in Cuba for much time.»

I was interested in addressing this moment in the book, the fast escalation of the belligerence between Cuba and the United States; the impact of the first policies of the revolutionary government and the reasons for the panic that led thousands of people who worked in entertainment and show business to leave Cuba or not return to it. It was an industry supported by gambling and run by the Italian-American mafia and it was being dismantled and alienated from its conception and essence.

In Celia, the decision to remain out of Cuba and go into exile came shortly after her departure. Like many figures of various levels in the Cuban music scene, she could not understand the measures of the new government, nor their consequences.

As you say, Celia Cruz is the most universal of Cuban performers; an icon that completed itself out of Cuba and that, however, represents Cubans so much… How do you explain that such a Cuban essence in her could continue to grow and expand despites being outside the island? Many musicians have said at times that without the Cuban public around they could not have created their work…

Authenticity is the only possible explanation. The pure sense of belonging that crystallizes in art, in a song, a rhythm, a musical genre, a way of singing and dancing, is something that, in my opinion, does not happen in the same way in later generations, more exposed to other influences and to the effects of living in a globalized world with permanent access to the largest information spectrum ever seen.

On the other hand, sometimes we think that the Cuban public is only on the island, and it is not so. Celia lived to see how her public grew and how it was filled more and more by new generations of Cubans who decided to live —and some were born— in other countries. Celia —and this is how I highlight it in the book— sang more to Cuba in the years that she lived outside of it.

If you study her repertoire, you could conclude that she felt the need to reaffirm her Cubanhood, her pride in her roots; it’s something she claimed on every stage in which she sang.

Hardworking, constant, tenacious, consecrated… I think these traits characterize Celia’s personality. For what other reasons is this woman (whom you have come to know like few others) admirable?

I interviewed many people who knew her, several women who were her friends and her colleagues. All, without any exception, expressed feelings of admiration and deep affection for her. This caught my attention, in particular, knowing how competitive the artistic field is and the mixed feelings that the success of others can provoke.

They all made reference to her simplicity, a trait that the fame and the money earnt did not change at all; her capacity for solidarity; her unrestricted support for her family, wherever she was.

Celia was a teacher who graduated from the Normal School for Teachers in Havana. There she developed her intelligence and her attachment to reading.

She was nice, witty, with a very Cuban sense of humor, but refined.

Many of those who knew her affirm that she as the artist on the stage was just that: the one on the stage. Although both were authentic, the everyday Celia exhibited intelligence, strict discipline, punctuality, depth of analysis, practicality, and professionalism as essential traits for her success.

Throughout her career, Celia interpreted songs that could be described as bearing a reactive feminism. Oftentimes she inverts or deactivates commonplaces of popular music, of masculine, patriarchal roots. How did this happen? Was it a process? What examples can illustrate this facet of Celia Cruz? What were her reasons?

I don’t think it was a premeditated process. It is true that from her own experience, Celia embodies that feminist struggle for recognition and respect for the personal and professional individuality of women.

She favored (and this is a remarkable fact) the presence of female composers in her repertoire with La Sonora Matancera, and even before with other formations, such as Gloria Matancera. That wasn’t a very common practice in orchestras and ensembles either.

With her fame, she helped those composers become known and their work turned into income from copyright.

But perhaps the most eloquent example of this reactive feminism is her interpretation of the guaracha «La Sopa en Botella», composed by a man, the great composer Senén Suárez, who was inspired by a guaguancó, «El vivebien», a hymn to machismo and the exploitation of women that had become very popular at the time.

Suárez decided to write a response —completely feminist— and «La Sopa en Botella» came out, designed —as he said back in the day— for Celia’s voice. Upon proposing it, Celia immediately accepted it and made it one of her most popular singles.

Having witnessed your work, I would dare to say that this has been one of your most laborious and complex endeavors. You confessed to me that sometimes when you were writing you felt close to Celia, strengthened by her. I imagined it as a communion between women who protect and help each other. Has it been like this?

I think so. I think that those energies of hers have reached me or, at least, I feel that the releasing of the book, seeing it in print, is her recognition of the honesty and dedication with which I approached the research and writing.

Celia’s example, as the image of a successful woman on a worldly scale based on her self-improvement and her commitment to her birth country’s musical culture, is very strong and inspiring. And that inspiration goes beyond our borders: it radiates to several generations of women, especially Cubans and Latin Americans.

This also connects with women’s struggles and aspirations and that goes beyond confluences or political differences. There is no censorship to that.

It was precisely this feeling that united us, the four women involved in the book: Tania Cordero, editor; Pilar Fernandez Melo; diagrammer and designer and Marietta González, collaborating on cover design and the concept of promotional elements. And —like the feminism that I like to practice and support— together with two essential men: Abel Ferro, designer of that beautiful cover, and Omer Pardillo Cid, head of the Celia Cruz Foundation, who believed in my project and gave me all the support to access Celia’s files as well as his own memories and experiences as her last manager, friend, almost son and executor of her legacy, which he honors with his actions.

* This interview was originally published in Matria